Romania: how a disinformation campaign prevented free suffrage

Romania: how a disinformation campaign prevented free suffrage16/12/2024

By Raluca Radu, ADB Romania & University of Bucharest

On 24 November 2024, in the first round of presidential elections, 23 Romanian citizens out of 100 who voted chose a candidate with no party, no electoral staff, no declared electoral budget and limited exposure in mainstream media. The news shocked everyone: over two million people chose Călin Georgescu, a candidate with virtually no chance to win under normal circumstances. After elections, he was presented in the news as a TikTok character, who promoted his electoral program from his living room. With no campaign headquarters, he interacted with journalists in front of a gate, in the streets of Izvorani, a village near Bucharest, the capital of Romania.

The next four presidential candidates were supported by the main four parliamentary parties. Their declared electoral expenses, combined, amount to almost 19,5 mil EUR. One of the candidates, who came third, is the Romanian Prime-minister, another one, who came fifth, is the President of the Senate and the former prime-minister.

Two days after the elections, TikTok CEO was summoned to the European Parliament, to explain the social network’s involvement in the Romanian electoral results.

Four days after the elections, the Supreme Council of National Defence (CSAT), gathered at the request of Klaus Iohannis, the President of Romania, issued a statement about ‘possible risks to national security generated by the actions of state and non-state cyber actors’. CSAT blamed TikTok for a preferential treatment for Călin Georgescu and for breaching Romanian electoral legislation.

Some of the documents presented in CSAT were declassified a week later, adding to the information from investigations led by journalists and civic activists unveiling a coordinated campaign, on several social networks, for Călin Georgescu. Journalists also discovered Georgescu’s neo-Nazi ties.

Călin Georgescu discourse, as it appears on social media and on video platforms, was analysed by media and by civic activists to identify pro-Russia, anti-NATO and anti-UE themes, mixed with numerous references to God, with pseudoscience and with a sovereignist approach to agriculture and economy. During the two weeks following the first round of the presidential elections, the Bucharest Stock Exchange was ‘in free fall’ according to Ziarul Financiar.

On Friday, December 6th, a few hours after the vote for the second round of elections started for the Romanian diaspora, the Constitutional Court annulled the whole presidential electoral process and ordered the elections to be rescheduled by the Romanian Government. The Court quoted a document of the Venice Commission, issued on the same day. This document, entitled ‘Interpretative declaration of the Code of good practice in electoral matters as concerns digital technologies and artificial intelligence’, stipulates that:

State authorities should address the challenge posed by organised information disorder campaigns, which have the potential to undermine the integrity of electoral processes.

How did a right-wing, online candidate win the lion share in the first round of Romanian presidential elections? Was he the beneficiary of an organised information disorder campaign? If TikTok is to blame, what is the mechanism that supported an online candidate win real, offline elections? How can we prevent coordinated disinformation campaigns, that lead to socking outcomes during electoral processes?

This is what we know.

The social platforms involved in the electoral campaign

Călin Georgescu was visible on TikTok, but also on Facebook or YouTube. Messages about Georgescu circulated, for several years now, on WhatsApp, with links about him to YouTube videos and alternative media websites. One of these videos was debunked in 2021 by mainstream newsrooms..

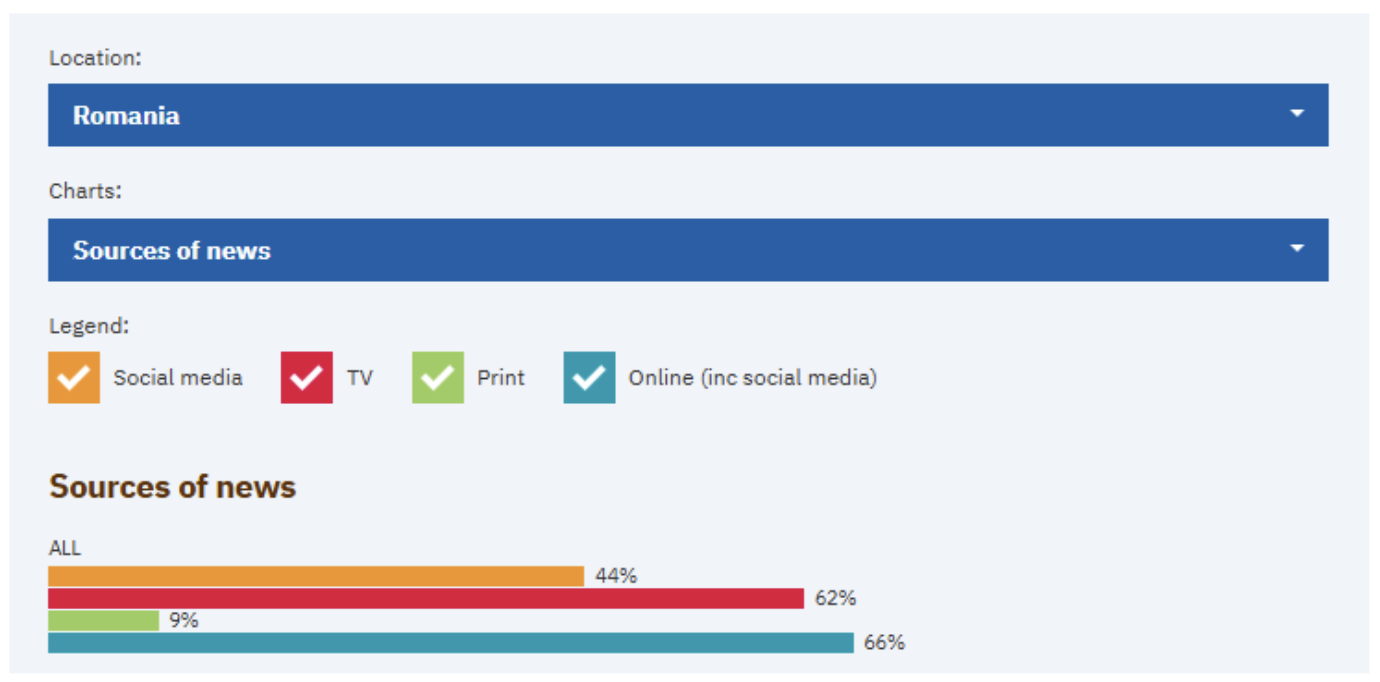

Since 2020, digital audiences worldwide have started to choose social platforms over mainstream newsrooms as the main access point for information and opinion, the Digital News Report (DNR) shows (DNR is the largest international, multi-annual survey of news related behaviour ; the study is coordinated by the Reuters Institute at the University of Oxford and covers over 40 media markets, including Romania). In January-February 2024, when the last DNR data were collected, in the top social brands used for any purpose in Romania were Facebook (64%), YouTube (56%), WhatsApp (56%), Facebook Messenger (54%), TikTok (31%), and Instagram (27%).

On social media, the audience is not actively looking for news. Instead, news find their audience. We are exposed to information and opinion on public affairs if the social platform algorithms identify some random content as relevant for us – alongside cats, dogs, food pictures, make-up reels, pictures with friends and, of course, advertising. Despite these well-known shortcoming, almost half of the Romanian sample declared they use social media for news, while six out of ten also indicate “television” as a source of information.

Digital News Report Data for 2024 show that almost half of the Romanian digital public uses social media for news [source]

Facebook, YouTube, TikTok, and Instagram are considered, in the European Union, Very Large Online Platforms (VLOPs) and have to obey the Digital Service Act - WhatsApp and Facebook Messenger are not covered by the DSA, which came into force in 2024) -, designed ‘to create a safer digital space where the fundamental rights of users are protected’. These fundamental rights include the right to be informed correctly and to have access to all viewpoints during elections. The other two networks favoured by Romanians, WhatsApp and Facebook Messenger, both from Meta, are peer-to-peer, not opened to scrutiny by authorities or academia.

A misleading message for the discontented

On social media and in his YouTube interviews, Georgescu used several older conspiracy theories (from the fake moon landing to 5G) and some new pieces of disinformation. He said, for example, that water is not just H2O. As described by his CV, Georgescu is a specialist in pollution, with a PhD in pedology (1999). His current employer is a public Romanian university.

The conspiracy theories Georgescu used were mixed with nationalistic and mystic messages, but also with anti-NATO and anti-UE messages. Lists of debated assertions, reaching up to 430 entries, are circulating online. There is also a site linking controversial statements to their sources, called What Călin Said.

Factual, the most preeminent Romanian fact-checking team, covered 32 statements of Călin Georgescu, from nanochips in soda drinks to death due to chemotherapy, and found just one to be partially true. This is the most extensive effort to fact-check the controversial declarations of Călin Georgescu.

From a researcher’s perspective, Georgescu’s use of a mystic, sovereignist discourse, mixed with conspiracy theories narratives, is important, because research shows that conspiracy theories are more salient for extreme left and extreme right-wing citizens. ‘This non-linear relation may be strengthened by, but is not reducible to, deprivation of political control’ explain Imhoff and his colleagues, in a 2022 scientific article.

So was Georgescu voted for by an unheard constituency leaning towards the extreme-right?

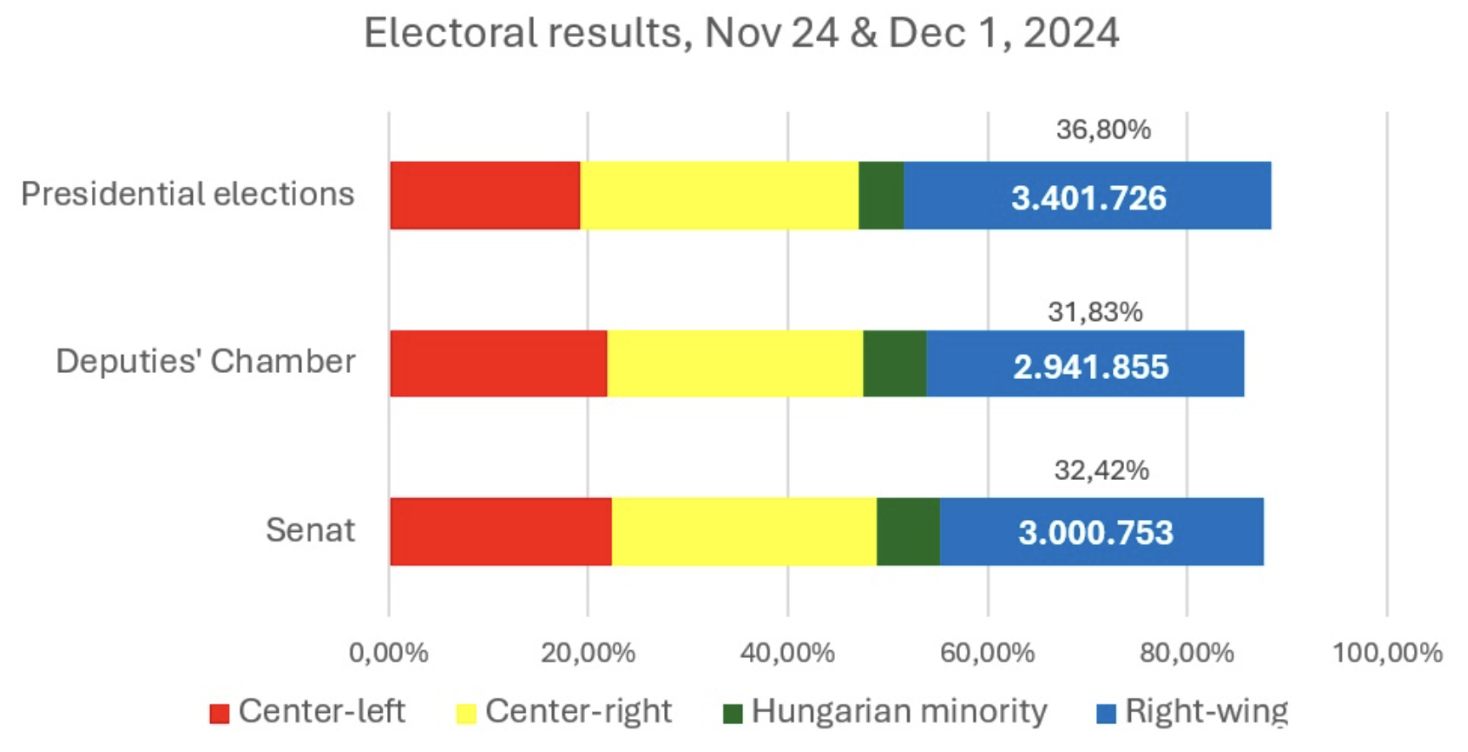

We gather the percentages won by Călin Georgescu and by George Simion, the leader of the Alliance for the Union of Romanians (AUR), the right-wing parliamentary party between 2020 and 2024. These two candidates gathered almost 37 percent of the votes, from 3.4 million voters, for the presidential elections on November 24.

If we add the percentage won by the three right-wing parties that exceeded the electoral threshold in the parliamentary elections one week later, we reach similar results. AUR, SOS Romania and the Party of Young People (POT), gathered almost 32 percent of the votes for both chambers of the Romanian Parliament, from about 3 million citizens.

The radicalized discontented during the November-December 2024 elections in Romania. There were 3 million voters who chose right-wing parties for the new Romanian parliament, out of almost 9.5 million voters present. Source: data from the Permanent Electoral Authority, with our own calculations.

SOS and POT were parties founded by ex-AUR members. Georgescu was also working with AUR, in the past. Members of AUR, for example, supported Călin Georgescu as a possible president of honour for the party, and prime-minister for Romania.

In the last elections, in 2020, about half a million people voted for the right-wing programmes. Four years later, 3.5 million chose a right-wing candidate and 3 million, a right-wing party. In 2024, the number of voters was almost double, as compared to 2020 (9.4 mil people voted for the Parliamentary elections this year; in 2020, there were 5.9 mil electors).

A campaign based on micro-influencers

Călin Georgescu was the beneficiary of a ‘coordinated dissemination on multiple platforms’, since June 2024. The coordinated dissemination was part of a campaign, understood as a planned process during which a target audience is exposed to the same message repeatedly, over a period of time. The intensity of this campaign increased in the two weeks before the voting day, shows a declassified document of the Romanian Intelligence Service.

The multiple platforms used for Georgescu’s presidential campaign included Tiktok, with political communication marked as entertainment/ information/ education, alongside Facebook, YouTube, Instagram, WhatsApp and Telegram, showed Expert Forum, a civic NGO, and G4Media, an investigative newsroom.

This campaign used influencers that were coordinated through platforms that included FameUp (linking brands to influencers) and Telegram, a closed social network.

Investigative reporters showed that on Telegram, one group, created to promote the candidature of Călin Georgescu, received over 1800 pictures and videos, to be edited (to be considered new content by algorithms) and reposted on organically grown environments (to be allowed by algorithms to grow further). People were paid based on a contest, other journalists from G4Media discovered.

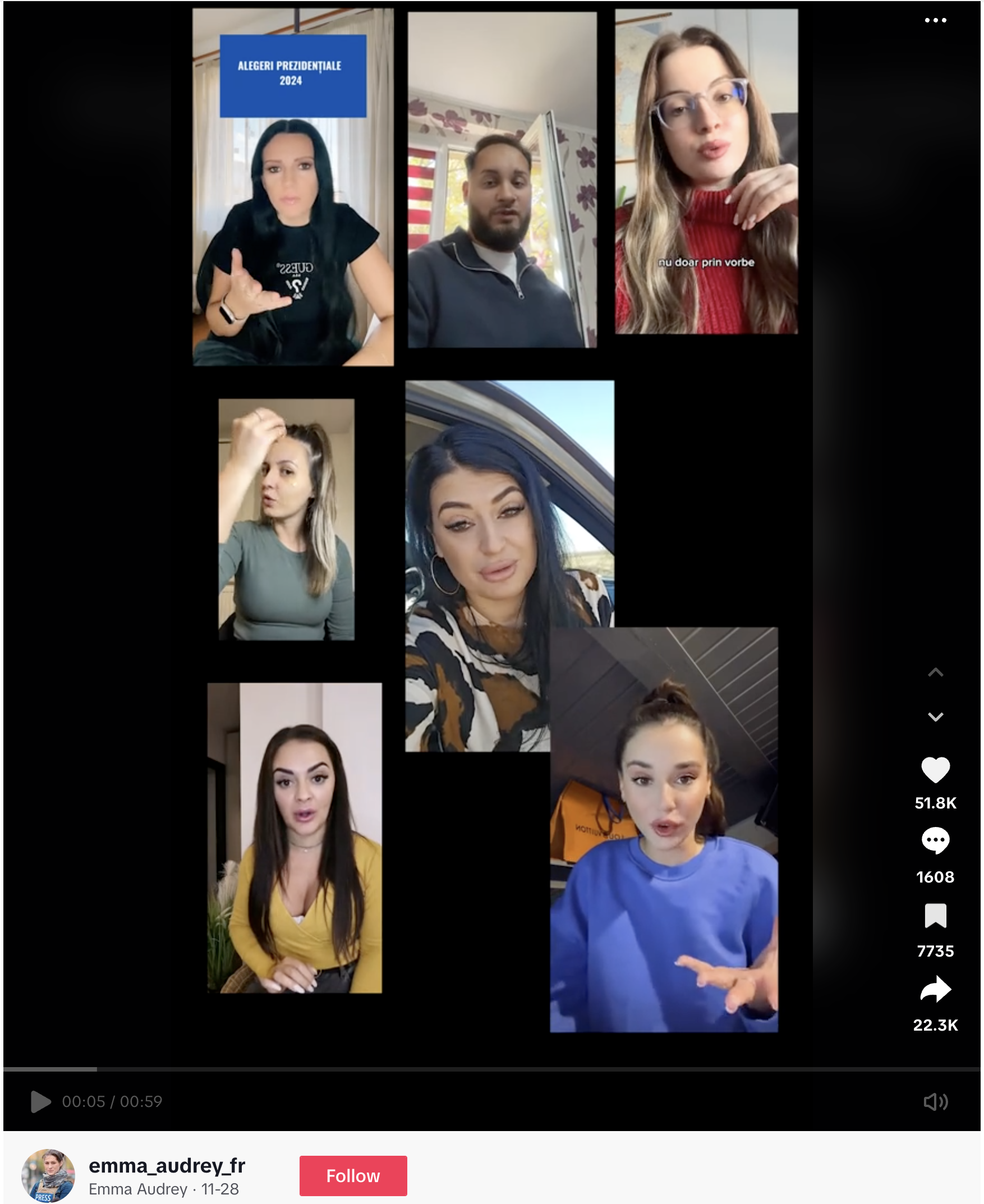

On FameUp, influencers received a script from two organizations that do not exist as officially recognised commercial companies in Romania. The names of the companies were made up. The proposed script recycled the messages of Călin Georgescu, without actually mentioning him, and imposed a hashtag, Equilibrium and Verticality. In the comments, people seemed to have difficulties in deciding who is the candidate supported by the influencers, journalists from HotNews showed.

The Ministry of Internal Affairs considers that the campaign Equilibrium and Verticality used the same methods as Brother Near Brother, the campaign Russia run in Ukraine: ‘both are based on the manipulation of legitimate micro-influencers’.

A selection of micro-influencers ironing, driving their cars or using make-up, while reading the script about presidential elections proposed on the FameUp platform, under the hashtag Equilibrium and Verticality.

Researchers have been trying for a long time to explain how mass-media influence decision-making processes – and how people chose whom to vote for. Paul Lazarsfeld and his team discovered in the 1950s that people are aware of media messages, but what these messages mean for them and how these messages influence their vote are the result of community-based opinion leaders.

During electoral campaigns, media indicate which are the important issues on the public agenda, the agenda setting theory of McCombs and Shaw postulated in 1972, and not necessarily how to position yourself on these issues.

Still, more recent research also shows that media characters may influence attitudes and behaviours in the short term – thus the concept of ‘parasocial opinion leaders’ was proposed by the communication studies scientific literature.

A parasocial opinion leader can be any character in mass-media, with whom we have no real interaction: a politician that looks human because he starts crying, or because she introduces us to her house or her children; a real person trolling a journalist on social media, while talking about his or her feelings in an exaggerated way; a serial drama persona that has the life we think we live or we would like to live; a bot with a profile with a nice cat and holidays at a beach saying - I am voting for Călin Georgescu – in fact, any character that seems similar to us, in some way.

The Romanian TikTok influencers used for Georgescu’s campaign were known for their interest in makeup, cars, fashion, entertainment, Expert Forum explains. They presented themselves online like normal people involved in day-to-day activities. They talk about an ideal candidate for presidency while ironing or applying make-up. We can see them in their car or in their kitchen. They are normal people, just like us, preparing for the voting day. We do not actually know them, but we feel they are our friends – thus, the parasocial relationship we developed with these media characters.

Can these parasocial opinion leaders influence the vote, as they influence how people dress or do their hair? Probably they can – for some members of the public, under specific conditions, with specific messages.

All presidential candidates were present on social media. Trolls and bots were used by several parties during the electoral campaign. One of the reasons that made the campaign for Georgescu so powerful was that Călin Georgescu had mostly positive coverage, as compared with his political rivals, adds Expert Forum. Georgescu was not attacked by his rivals, because he was not considered a dangerous opponent, until it was too late, and his voters were already radicalised.

Who is behind Georgescu’s campaign?

On November 28, the Supreme Council of National Defence issued a statement about possible interference of ‘state and non-state cyber actors’, that affected the electoral process in Romania. Two weeks later, journalists remarked that no authority presented any proof about a foreign influence on the electoral process.

Investigative journalists and civic activists from Romania, Bulgaria and France presented possible links between online advertising companies, active in Eastern Europe, and Russia. Experts analysing the electoral campaign told journalists that ‘in the promotion of Călin Georgescu, networks affiliated with Russia and beyond, specialized in destabilizing democracies, were involved’. Romanian authorities are now investigating where the money that financed the online campaign for Călin Georgescu came from. A Romanian cryptocurrency investor was identified as one of the donors, but he sustained that he offered money on TikTok to promoters of several candidates, not only of Georgescu. The FameUp platform is also under investigation. According to journalists from Snoop, fiscal authorities discovered that the National Liberal Party (PNL) paid for the TikTok campaign Equilibrium and Verticality that promoted Călin Georgescu. The communication company that works for PNL admitted the payments, and asked for an official inquiry, to verify if its campaign was 'cloned or hijacked'. The National Liberal Party formed with the Social Democratic Party a ruling coalition in 2021. Klaus Iohannis, the acting Romania President, is a former member of PNL.

Romanian electoral authorities remarked, before the first round of elections, that Călin Georgescu was promoted illegally – this is, without a compulsory mark that indicated the promotional materials were part of an electoral campaign. Authorities asked Facebook (owned by Meta) and TikTok (owned by ByteDance) to stop the materials, but TikTok did not comply.

After the elections, TikTok declined any responsibility related to Presidential elections in Romania, saying that they do not allow political advertising and that they are very vigilant in their effort to block misleading behaviours. Nevertheless, two investigative journalists, from Recorder and Snoop, showed that TikTok seems to have a security breach that can be used to easily create fake accounts and to use bots that can boost a (fake) candidate to 1 million views in less than two hours.

These revelations make the discussion about possible influences on the electoral processes even more complex.

We tend to link social platforms to market economy and algorithms to profit. Yet, media products are not always created and distributed within a profit-making mindset. Newsrooms, for example, may cater for the general public interest, may be part of a profit-based commercial enterprise but may also be instrumentalised for political or economic interests – propaganda included. Maybe it is time to apply the same vision to social media, not only to traditional media. If states own and control traditional media for influence, why would they refrain from owning or controlling social platforms?

In fact, algorithms may be used to promote or restrict viewpoints, persons, causes, narratives - for influence, as well as for profit. Virality can be paid for, by interested parties.

What investigative reporters and digital activists demonstrated, in the aftermath of Romanian elections, is that with the adequate resources, social platforms algorithms can be manipulated to target a specific public with a mix of messages that end up influencing the free suffrage in a country.

Authorities are responsible to find who is behind online manipulation of electoral processes, in the present, and to prevent similar events, in the future.

Lessons learned during the Romanian 2024 presidential elections

What we understand now, after the sock of the Romanian electoral process, is that:

Journalists and civic activists can not debunk hundreds of misleading pieces of information, launched in avalanche, during a coordinated campaign. Of course, journalists and civic activists can fact-check main allegations, to warn about the messages and the intentions of a dangerous source of misinformation, with increased virality. An early warning could be very helpful, the inoculation theory sustains.

Conspiracy theories and misleading pieces of information may be part of a coordinated campaign getting viral on multiple platforms. Călin Georgescu’s campaign was not solely on TikTok. He was constantly covered by traditional media, due to his ties to the right-wing party and to his videos on social media. Links to YouTube videos with Georgescu interviews have been circulating on WhatsApp for many years now. He might be regarded as a TiKTok candidate mainly because TikTok refused to delete his promotional messages, three days before elections. Georgescu’s campaign on TikTok is the main one opened for public scrutiny, but TikTok is not the sole platform he used. Civic activists and journalists showed Georgescu was present on TikTok, but also on Facebook, YouTube, Instagram, WhatsApp and Telegram.

Parasocial opinion leaders may be used in electoral campaigns, to distribute preexisting electoral content. These parasocial opinion leaders include micro-influencers, trolls and bots, alongside political leaders and normal social media users, that support an idea, a candidate, a political platform or a cause, in an excessive, yet relatable way for other social media users.

Political content might appear in posts, in videos, in comments, in (native) advertising – in all types of materials distributed by social platforms. Just because a social platform declares all content to be entertainment, or a micro-influencer is known for his or her content on makeup and cars, does not mean the platform will never host political content or the influencer will not share political recommendations, for an advertising fee.

Previous research on echo chambers, parasocial opinion leaders and the inoculation theory (see Radu, 2023) shows that viral content from parasocial opinion leaders rely on radicalising strategies and excessive public behaviour.

The strategies that push a person to choose one side or another, in a public issue, include the identification of an enemy, the identification of a threat, rebutting an opposing communication frame and the validation of inner group members. All these strategies are often used during the electoral process, to determine voting behaviour, but Georgescu’s campaign was more successful than usual.

One of the reasons for Georgescu’s success might be the use of parasocial opinion leaders, with excessive public behaviour that made them seem more human and more relatable for the members of a discontented constituency. This behaviour included inflaming vocabulary and strong negative emotions, targeted against the political rivals of Geogescu, and the exhibition of a transgressive intimate self. Bots, trolls and micro-influencers discussed publicly a personal choice, often kept private: whom they intend to vote and why. To seem more human, some of them staged the exhibition of private details: what is their relationship with God, how do they iron a piece of cloth, how their kitchen looks or how they put makeup on.

Of course, anyone is allowed to present any piece of information about their private lives online, if they keep their presence within the lines of the law. Georgescu’s campaign was, in fact, illegal in Romania, because citizens exposed to his messages were not warned they were exposed to paid content.

It is highly possible that Artificial Intelligence (AI) can be trained to monitor key terms like party names, political candidates, alongside public issues like peace, war, Ukraine or Palestine, that seem to get viral, in one geographic area, on multiple platforms at once.

Journalists and civic activists could be helped by a platform showing them what the public sees on multiple social media, on a given geographical area, at a given moment, in a transparency process like the one used by Google, with its Google Trends.

Additionally, AI can be used to diagnose the environments where key terms appear – for example, if key terms are growing viral with the help of parasocial opinion leaders, as part of a possible disinformation campaign with radicalising aims.

This way, journalists, civic activists, authorities and the general public can be warned in due time of possible ‘information disorder campaigns, which have the potential to undermine the integrity of electoral processes’ (as the Venice Commission indicated) or the integrity of any other public discussion on key, public interest issues.